The Violence of Sameness: How Algorithmic Media Amplifies Mimetic Rivalry

Navigating Fragmented Reality in the Attention Economy

Summary

René Girard's mimetic theory illuminates how localized human communication networks evolved into today's algorithm-driven social media landscape, shifting the mediation of mimetic desire from religious institutions to mass media conglomerates and now to personalized digital ecosystems. Modern algorithmic media platforms amplify mimetic rivalries without the traditional restraining mechanisms, generating novel social divisions that will require innovative solutions to mediate our innate human tendency to violence.

The Mimetic Engine of Desire, Mediation & Violence

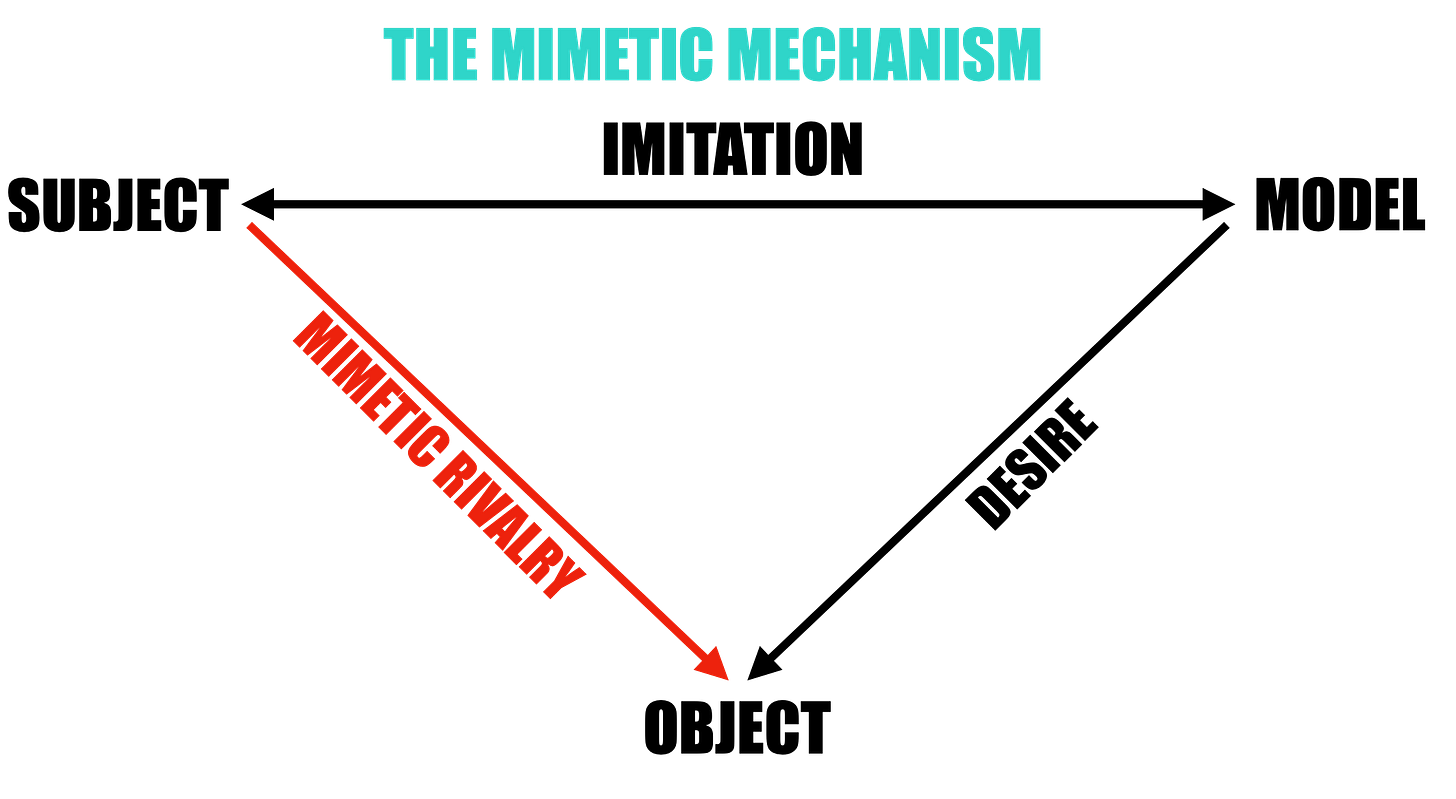

René Girard's mimetic theory proposes that human desire is fundamentally imitative rather than autonomous. We desire objects and experiences not for their inherent value but because others—our models—desire them. This mimetic nature forms the bonds of friendship and love that connect us while, simultaneously, containing the seeds of violence if desires converge on objects that cannot be shared. 1

When humans mirror models of desire with others in close proximity, there is a tendency towards competition for the same objects, leading to what Girard called "mimetic rivalry." As these rivalries intensify, they can spread contagiously throughout a community, creating a mimetic crises that threatens social stability. Girard proposes that this triangular relationship between subject, model, and object is the fundamental driver both human culture and human violence.

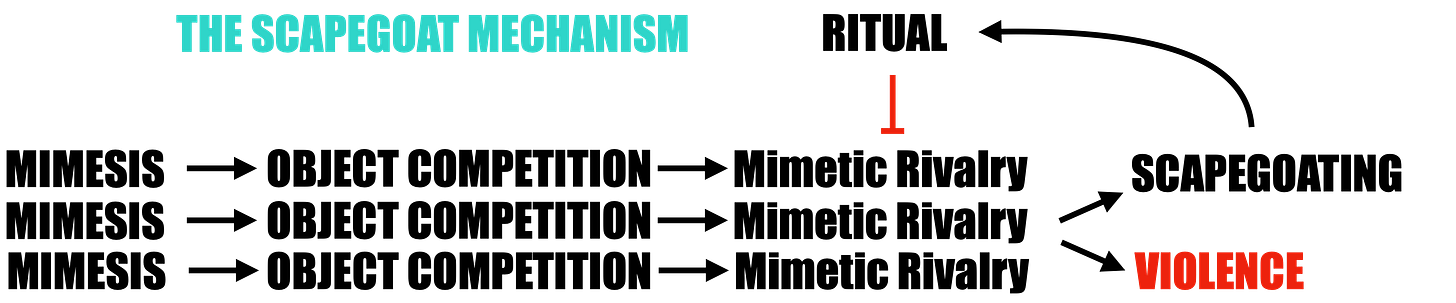

To prevent self-destruction from escalating rivalry, human societies developed the scapegoat mechanism—identifying and sacrificing victims whose elimination temporarily restores social harmony. The scapegoat mechanism appears with remarkable consistency across differing human cultures, where scapegoating became institutionalized in religious rituals, cultural prohibitions, and social norms.

Sacrificial rituals thus serve as societal safety mechanisms, channeling destructive mimetic competition away from the community while simultaneously strengthening group cohesion through collective participation in sanctioned victimization.

The universally acknowledged human tendencies toward envy and acquisitiveness suggest that Mimetic conflict may actually be an essential regulatory mechanism rather than a defect in human nature.

Human societies across time and space independently discovered the scapegoating mechanism, typically encoded in religious frameworks, to mediate mimetic desires and constrain violence. This suggests that (a) mimesis and violence is built into our biological hardware (b) is a regulatory feature rather not a bug (c) human beings create religion to shelter society from itself in the same way birds build nests.

The standard account of conflict is violence arises when people fight about differences. However, the key insight of mimetic theory is violence arises within society when people fight about the same thing.

The Transmission Rails of Mimesis

Mimesis requires informational transmission rails to communicate desires. Individuals use the same biological perceptual sensory apparatus wired directly into our neurocognitive social hardware, such as the mirror neuron network. At the scale of community, knowledge historically existed primarily through oral traditions, with essential cultural wisdom and understanding passed between generations through narrative and storytelling.

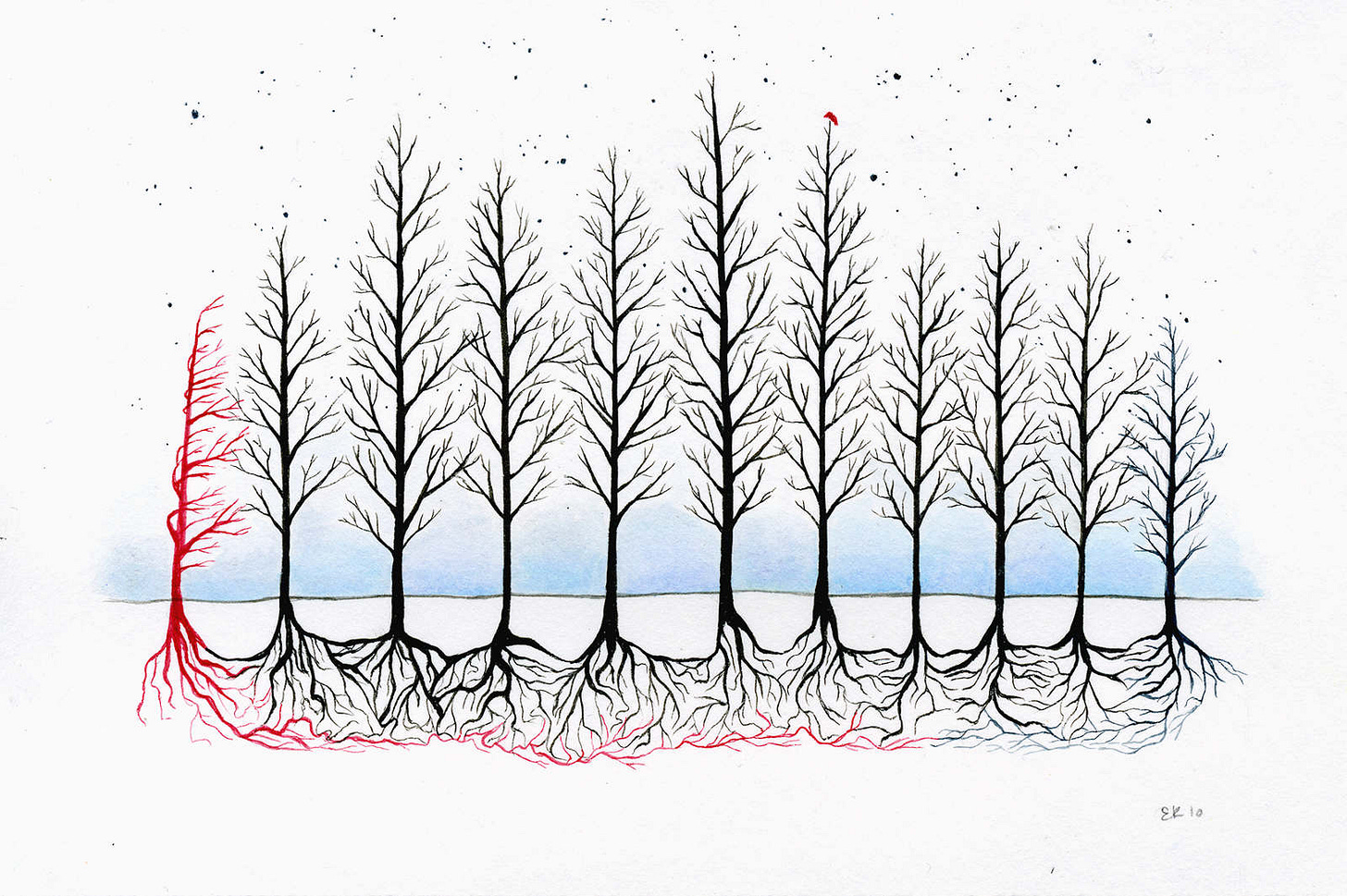

Communication networks function as evolutionary operating platforms that solve large-scale coordination problems in nature. This design recurs throughout biology because individuals cannot perceive all relevant environmental changes through observation alone. 2

A network of interconnected organisms exploring their environment possesses a significant survival advantage over solitary individuals. When 100 organisms function as a coordinated system, they collectively perceive and understand reality beyond any single member's observations, capturing a crucial survival premium through shared intelligence.

Many plant systems demonstrate this type of collective unconscious, as seen in the interconnected root system of individual aspen trees that practically function as a single organism.

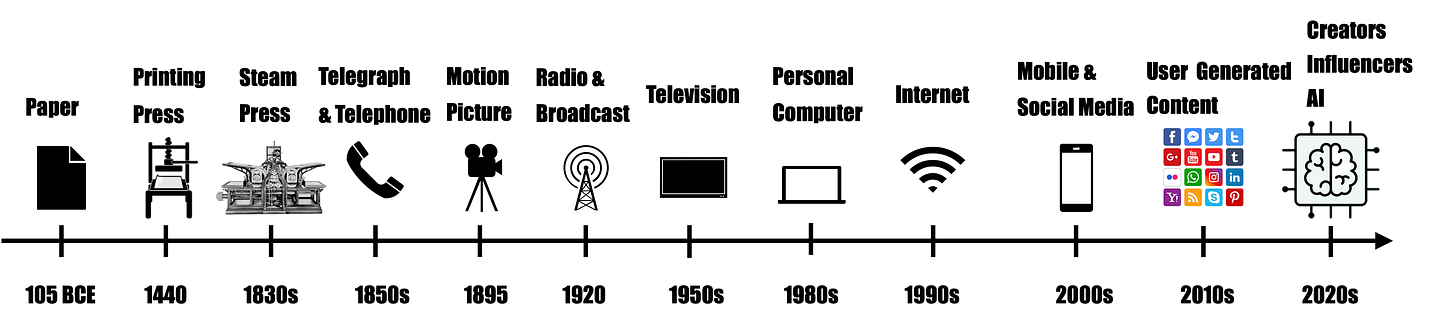

As our species harvested an increasing survival premium via communication networks, the newly available energetic surplus was directed towards developing more sophisticated information-sharing technologies, the advancement of which has recently gone parabolic.

The printing press enabled mass reproduction of printed media, though access initially remained limited to institutions and higher social classes.

Steam-powered presses during the Industrial Revolution democratized printed media by making it both affordable and accessible to the broader public.

The telegraph and telephone later created channels to transmit information instantly across vast distances, while radio and television transformed the very forms of content available for audience consumption.

Each breakthrough in communication technology fundamentally reshaped the infrastructure of information transmission, as systems naturally evolve to integrate the most advanced available methods while simultaneously cannibalizing the old technology.

From this communication revolution emerged mass media, a sophisticated ecosystem for collective observation-sharing that enables millions to simultaneously witness events and process developments in real time, transcending previous constraints of time and space. The fundamental value proposition of mass media is simple: quality information creates clearer perception of reality, enhancing decision-making abilities across both individual and collective levels.

With each improvement in bandwidth, latency, network topologies, and propagation speed the velocity of data moving throughout human network began to accelerate. In the era of spoken stories, network information flow was constrained by the physics of sound waves.

After the scientific revolution, information began to flow at the speed of light. 3

Sacred Mediators: Mass Media's Rise as Society's Mimetic Arbiters

As modern society secularized and traditional religious constraints on mimetic desire weakened, new institutions emerged to channel and mediate society-wide human desires. Mass media networks became foremost among these new mediators, simultaneously offering models of desire while regulating social tensions through controlled narratives. The Boomer nostalgia for post-World War II mid-century America is nostalgia for an entire country collectively orienting along the same few TV channels and news outlets.

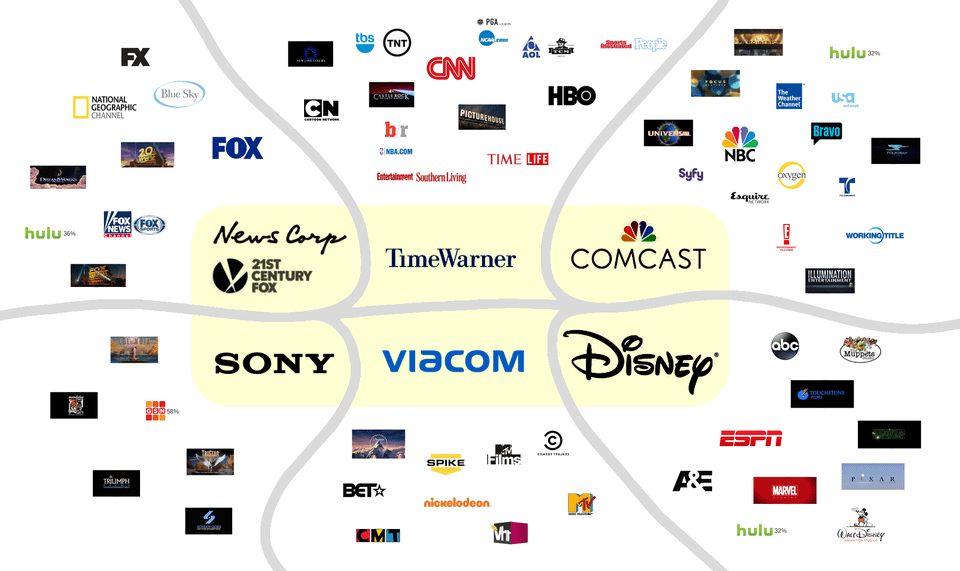

Girard would recognize mass media institutions as serving a quasi-religious function in managing societal desire. Just as the Catholic Church historically monopolized mediation between individuals and God through systematic power consolidation, mass media companies came to consolidate the flow of information to society into a entire vertical infrastructure, paving the way for their monopoly of economic and mimetic mediation. This was accomplished through three primary mechanisms:

First, mass media companies controlled physical distribution channels—printing presses, broadcast networks, cable infrastructure—creating high barriers to entry that gave them monopolistic control over which models of desire received widespread attention. 4

Second, they established institutional credibility through consistent practices, effectively forming a cartel of "mimetic arbitration"—determining which desires were legitimate and which were taboo. 5

Third, they captured advertising markets through bundling, systematically channeling mimetic desire toward commercial ends while maintaining the appearance of editorial independence.

Today, just six companies control 90% of traditional media outlets.

These monopolistic dynamics allowed media companies to extract extraordinary value via advertising while portraying themselves as a shining city on a hill; trusted public services, despite the glaring conflicts of interest.

Critical theorists who assail these institutions for such conflict of interest, for example Noam Chomsky, generally fail to recognize mass media as not just economic monopolies but also as necessary mediators of mimetic desire—serving as society wide violence dampeners in the same way religion once did. By building an economic monopoly, traditional media came to function as what Girard called an "external mediator"— constructing models of desire for the entire herd to create societal cohesion without triggering destructive rivalries and preventing runaway mimetic contagion.

Today, the monopolistic grip held by traditional mass media has begun to loosen under pressure from highly personalized content delivery algorithms known as social media.

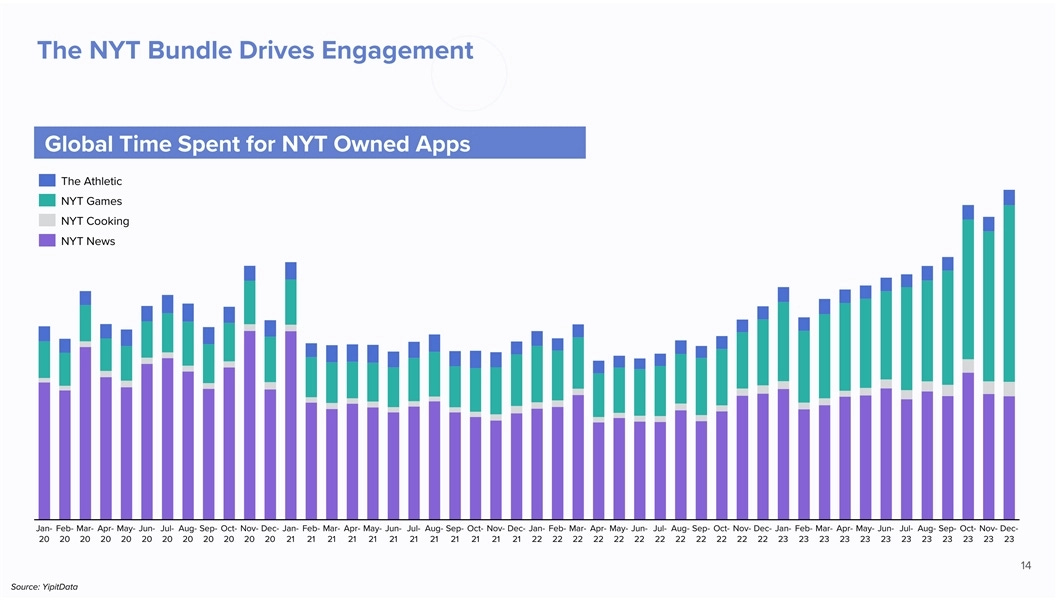

This dramatic shift is vividly illustrated in the revenue streams of traditional media companies like The New York Times, which now derives over half its revenue from digital subscriptions to online games and puzzles rather than from its traditional news content. Even the most established gatekeepers of information must adapt to a media ecosystem where personalized engagement increasingly displaces centralized editorial authority as the primary economic and mimetic mechanism in society. 6

The Mimetic Crisis of the 21st Century: The Fragmentation of Shared Reality by Algorithmic Amplification

Algorithmic social media represents a fundamental paradigm shift: while traditional media competed through curating scarcity, algorithmic systems compete by personalizing abundance. This inversion creates a Faustian bargain—offering unprecedented access to tailored content while fragmenting shared reality and intensifying desires through hyper-targeted models operating below conscious awareness.

Goethe’s “Faust and Mephistopheles”, 1827-1828, oil on canvas

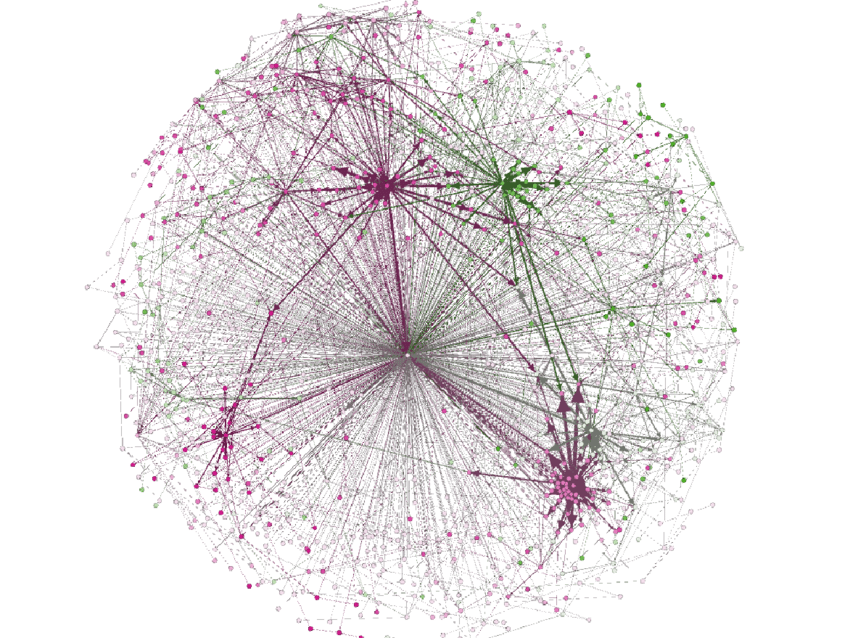

These systems iteratively improve to detect emerging desires and amplify them through engagement-optimized feedback loops. While "engagement" sounds neutral, algorithms systematically orient users toward like-minded communities, forming content clusters that reinforce existing beliefs. The result is divergent information diets where two users of the same platform experience fundamentally different realities.

A social network graph with content clusters based on user engagement

These digital spaces aren't merely echo chambers but mimetic incubators where desires and fears compound without traditional constraints. Algorithms function as what Girard would call "model-mediators," simultaneously suggesting what to desire, identifying scapegoats, and intensifying these impulses through social proof. Consequently, citizens downstream of their media diets lose control over their own beliefs and desires.

The scapegoat mechanism manifests vividly in internet cancel culture: the decentralized collective targeting of individuals who cannot effectively defend against anonymous swarms. The shared moral righteousness of a digital lynch mob reinforces the unity of their group in a shared belief in the scapegoat's guilt. It’s not surprising that a digital lynch mob constructed in binary bits, rather than atoms, does not speak nuance.

This creates a mimetic crisis where ideological echo chambers align and entrench users against different scapegoats and desire amplification outpaces society's ability to channel it productively.

The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1602 by Caravaggio, the canonical scapegoat examples in Western Judeo-Christian civilization include the binding of Isaac by Abraham or the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

What is perceived as a cultural or political crisis is actually mimetic acceleration now operating without traditional constraints. Political polarization, culture wars, and weekly viral outrage cycles are all symptoms of unregulated mimetic contagion.

Where traditional media monopolized physical distribution, algorithmic systems monopolize attention distribution—creating an economy operating largely below conscious awareness. Users engage in continuous transactions with every scroll and click, paying not in dollars but in time.

The New Media Monopoly

What we're witnessing is not informational democratization, as was the hope of the early internet, but its reconfiguration into a never before witnessed monopolistic architecture. Within the algorithmic ecosystem, new monopolistic nodes are forming—individuals and organizations accumulating disproportionate influence through algorithmic distribution's compounding advantages.

While traditional media competed within geographic boundaries, algorithmic platforms operate globally with virtually zero marginal distribution costs, creating unprecedented winner-take-all dynamics.

In attention markets, differentiation creates monopolistic niches, making the emerging horizontal monopoly of social media algorithms simultaneously more powerful and less visible. Joe Rogan exemplifies this shift—his distinction stems not merely from institutional independence and a very high IQ but from mastering algorithmic distribution mechanics while self portraying as a meathead.

From a Girardian perspective, we need better desire mediators—not better content filters—systems that acknowledge humanity's mimetic nature while channeling it toward non-rivalrous ends. The fundamental question becomes whether society can develop new mechanisms to manage accelerating mimetic desire in the algorithmic age.

In the 1891 book “The Decay of Lying,” Oscar Wilde articulates an anti-mimetic vision of the artist:

“Art doesn’t imitate life, as the saying goes—life imitates art,” according to Wilde. The artist is a creator par excellence. The artist brings new realities into being and changes how we see and experience the world. The artist enters unexplored wilderness and returns with a map, if he returns at all.

Most proposed solutions misidentify the problem by focusing on content moderation or platform regulation. The core issue isn't the content itself but the intensification of mimetic desire without corresponding mechanisms to manage mimetic rivalry. Mimetic aggression is the easiest of all mimesis; a free and loving anti-mimetic response has the power to change hearts and minds. In short, the problem lies not with technology but within the hearts of men.

The task at hand is to beat contagious mimetic rivalry without the traditional pressure release mechanism used by society historically. Girard succinctly lays out the challenge: “Everyone leaves the beaten path only to fall into the same ditch.”

Don’t get lost in the hall of mirrors, for there are many here amongst us who have yet to return.

The discovery of a reciprocal mirror neuron system built into our neurological hardware strongly supports Girard’s claims.

In practice, libertarians are always outcompeted by groups that can coordinate at scale. It’s the same problem of Bill Hick’s people who hate people party.

Most analyses of media evolution stop here, simply cataloging technological innovations without deeper examination. Yet this approach misses a crucial pattern: as media networks expanded from localized systems to global infrastructure, they didn't merely grow larger—they underwent a fundamental phase transition that transformed their essential characteristics into something entirely unprecedented in the history of human communications.

This represents the "means of production" from a Marxist perspective.

In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, Noam Chomsky outlines the propaganda model to explain how populations are manipulated and how consent for economic, social, and political policies, both foreign and domestic, is "manufactured" in the public mind.

Traditional media operated as vertical monopolies—controlling the full stack from content creation to distribution. Algorithmic platforms operate as horizontal monopolies—controlling a single layer (attention routing) across all content categories.

In the traditional model, news media flowed from primary sources through editorial filters before reaching the public. Wire service reporting involved journalists observing events and interviewing sources firsthand, while press releases from corporations and governments served as official information sources. Editorial staff chose which stories to cover, assigned resources, and set priorities, with wire content published through newspapers, websites, and specialized publications.

Many traditional media companies built credibility through decades of consistent, verifiable reporting and strict institutional practices. Their print subscription and advertising business models enabled them to prioritize quality over speed, establishing and maintaining credibility. Ownership of physical distribution channels and high barriers to entry established them as de facto information gatekeepers, creating a news cycle that was methodical and steady.

As algorithms became dominant attention-grabbers, they became the new filter between traditional media and audiences. Speed began to trump accuracy as newsrooms raced to break stories on social media, sometimes amplifying misinformation. Companies that survived oriented coverage toward partisan audiences to maintain relevance rather than focus on properly informing the public. This created a double-bind, where traditional media companies must either engage in modern tactics or risk financial collapse.