A Simple Framework for Effective Decision Making

Disentangling Outcomes From Decisions and Apply a Proven Game Plan

Always Disentangle Outcomes From Decisions

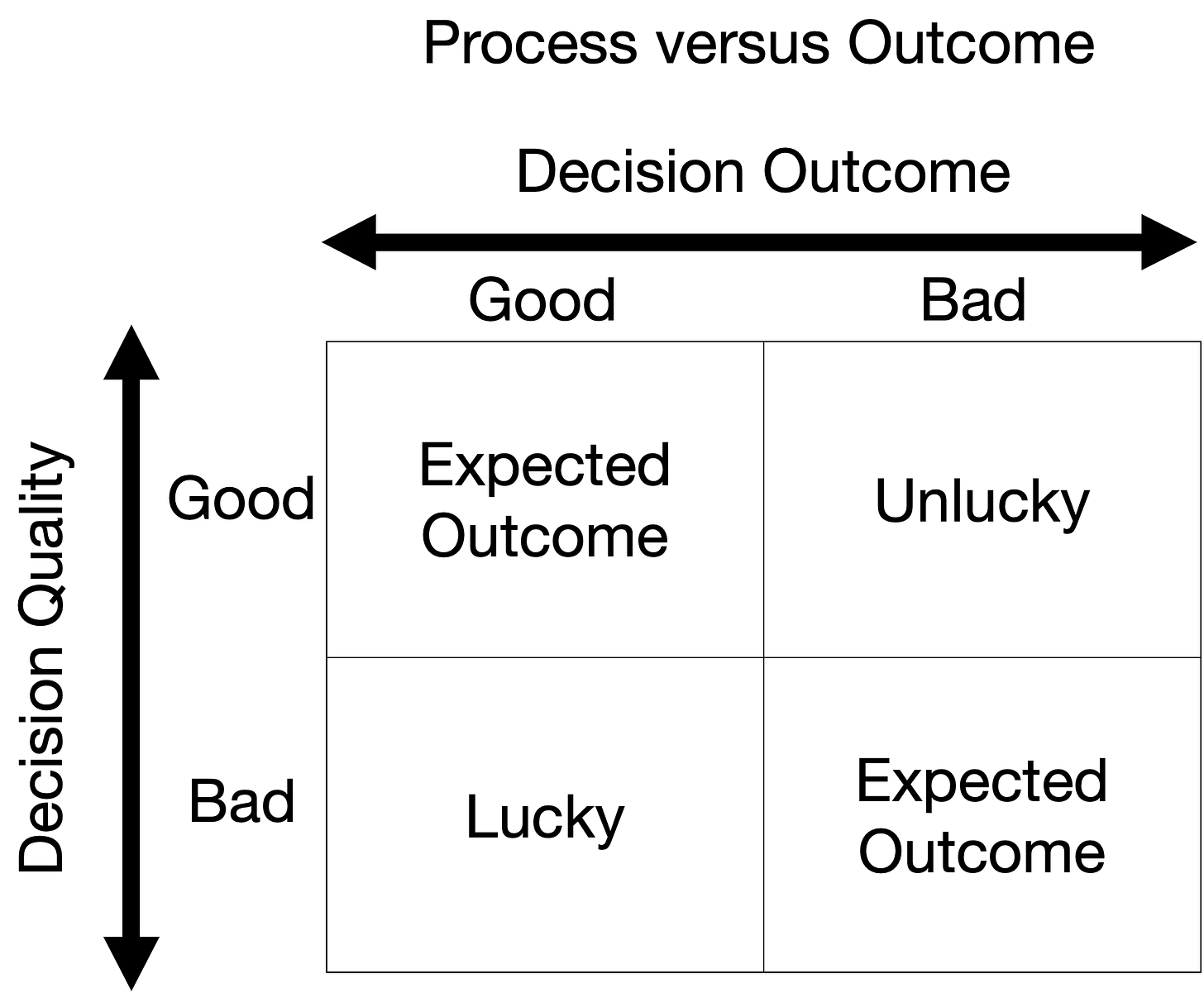

A common error in human judgment is using the quality of an outcome to judge the quality of a decision.

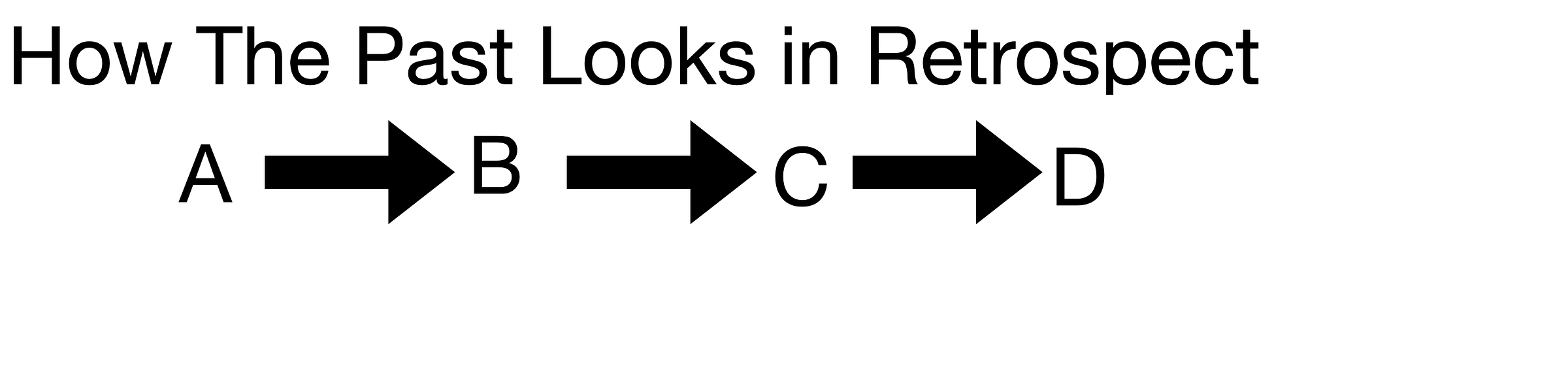

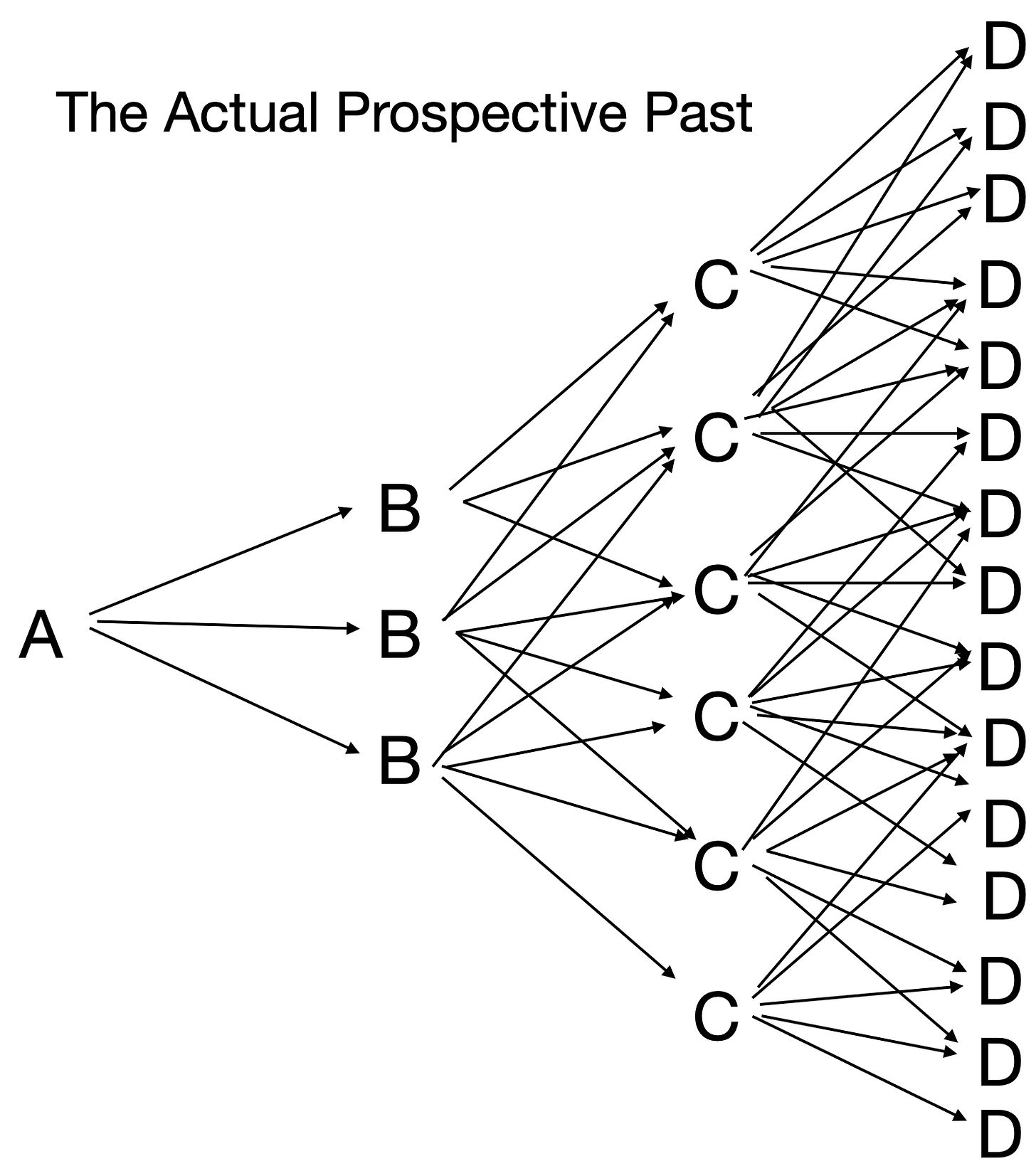

Failing to disentangle outcomes from decisions leads to retrospective distortions and hindsight bias. Hindsight bias changes our perception of a decision, making us see a singular outcome as an inevitable chain of events. This is the ubiquitous Monday morning quarterback syndrome.

Without disentangling outcome from the decision, it’s extremely difficult to disentangle luck from skill or a faulty decision making method.

For example, how do you know a good outcome was due to a brilliant strategic insight or blind luck? How do you know if a bad outcome was actually a tough break versus a long shot in the dark.

Without disentanglement, the whole process bleeds into a narrative you tell yourself after the fact. When judging personal decisions, hindsight bias tends to attribute good outcomes to skill and bad outcomes to luck (and vice versa when judging others).

Both retrospectively and prospectively we are wired to think discretely in a probabilistic world.

The vast majority of people are never taught how to make decisions. Without a framework the tendency is to fall prey to biases and blindspots. So let’s consider a decision making framework using expected payoffs. This framework is similar to the decision making process in a game like poker.

A Simple Decision-Making Game Plan

Determine all possible outcomes for decision.

Identify the potential payoffs for each outcome.

Estimate the probability of each outcome occurring. Use historical base rates if applicable and available.

Calculate the expected payoff for each outcome by multiplying the payoff value by the outcome probability.

Compare the expected payoffs between all potential outcomes

It’s important to know whether you are playing a finite or infinite game.

Repeat the process for each possible decision and compare the expected payoffs between all decisions and outcomes

See this page for a sample scenario with numbers.

Some Additional Decision Making Frameworks & Tools

Keep a decision journal for small and large decisions using base rates, perspective taking, counterfactual thinking and pre and post mortem analysis.

Write down the information you currently have, the risks you foresee and your decision making thought process because once the outcome is known your brain will retroactively distort what you actually knew and felt before the outcome occurred. Write it all down so you have evidence of your reasoning. Similar to cognitive behavioral therapy, this alone can expose distortions once it’s out of your head and on paper.

If available, figure out the base rate for the decision you’re trying to make. For example, if you’re worried about a specific medical complication following routine surgery, find the complication incidence to inform your expected value calculations.

Use perspective taking to get outside your personal worldview and biases. Consider in your imagination what a different decision maker, stake holder or someone you admire for their judgment might decide in the same situation. If seeking guidance from a friend or mentor, don’t first disclose your thought process to avoid corrupting their opinion.

In medicine, a post mortem is an autopsy of a body to determine the cause of death retrospectively. Organizational strategists similarly use this practice to dissect out why a company decision went off the rails. Write postmortems for your decisions regardless of the outcome. Use counterfactual thinking. This is similar to writing an “alternative history.” Consider hypothetical scenarios where an alternative outcomes occurred and find insights by viewing your decision process through a different outcome lens. The human tendency to rumination, regret or self pity when reflecting on the past is an unhealthy version counterfactual thinking where one digs a psychological hole that you will just have to dig yourself out of later.

Instead of a postmortem, you can also generate a pre mortem where you write up a hypothetical future postmortem forecasting why a decision went awry. Research by J. Russo at Cornell found prospective hindsight - which you imagine an outcome has already occurred - increases accurate forecasting of decision failure points by 30%.

Jeff Bezos uses the frame of one way vs two way doors:

Two way door decisions are reversible and should be made quickly. If it’s the wrong decision you can always go back.

One way door decisions are impossible to reverse once made or would be extremely complicated and costly to reverse, so are extremely consequential. These decisions should be made deliberately and carefully.

Organizations and people make a frequent error by treating two way door decisions like one way door decisions.

Each additional unit of information you seek out becomes less valuable and more costly to obtain, so consider setting a target of having 70% of the information you need to make a decision for a two way door. It’s rare to have perfect information.

The one versus two way door frame relates to the finite versus iterative game mental model.

Ask yourself if your decisions exhibits path dependency i.e. each decision alters future decisions,

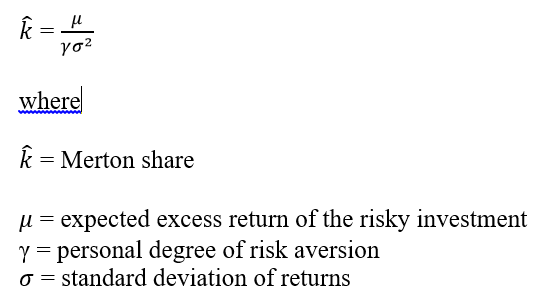

Per the “Merton share,” named after the Nobel-winning economist Robert Merton, “the expected profit required from a gamble increases not with the size of the risk, but rather with the size of the risk squared.” Said another way, risk moves up exponentially not linearly in relation to your expected payoff.

Be aware of the paradox of choice, where having too many options can lead to negative outcomes, such as anxiety, decision paralysis, and dissatisfaction through higher expectations. An interesting example of this is how lifetime sexual partners is inversely correlated with martial happiness. Spouses who are both each other’s first and only sexual partner tend to have happier marriages. Defend against this by simplifying options (make the one choice that eliminates a thousand choices) and be a "satisficer" versus a "maximizer."

If you are really struggling to choose between an array of decisions, consider the mathematical tool of inversion, often required to solve algebraic equations. Instead of asking “What good decisions must I make to achieve my target outcome”, ask “What bad decisions could I make to ensure I fail at this?” At a minimum it helps set parameters or constraints on the decision making process by eliminating bad decisions. Charlie Munger famously delivered a graduation speech through the lens of inversion titled “How to Guarantee a Life of Misery.” This included prescriptions like “go down and stay down” and “be unreliable.”